“Linux is a beautiful operating system,” said P, a kindly tech trainer with gray hair from the UK, “because it is held together by our trust in each other.”

We sat together in a workshop on email encryption – Thunderbird, to Enigmail, via Seahorse. The registration of public and private keys. Sharing keys in our very first “cryptoparty.” It felt like the iniation to a secret club. I will sign your key, and you will sign my key – and we will help verify each other, so that people who know you will know that I am also safe.

Safety is a responsibility we have towards each other.

“I think I’m going to revoke my key,” P told me. “I’ve been too careless with it the last few years, and I know there are people here who are in truly vulnerable contexts, so I want to take extra protections. Safety in networks means that you’re only as safe as the weakest link.”

The protection we find in each other is all that we have. Even more important than technical security are the practices of interpersonal safety and mutual care. Of course, this is also a liability, because you are only as strong as your weakest link. Sending an email from a PGP-secured email account to a gmail account would make you vulnerable. And having the signatures of vulnerable activists on your email key can also put these activists in circles of surveillance as well as webs of trust.

In the morning, we talked about the safety of our bodies, and shared information about how networks of sex workers keep bad date lists to warn each other of violent clients and undercover police. We made a little skit to demonstrate our strategies for safety. In our skit, a street worker is assaulted by the police, and another sex worker has to stand from behind a car to secretly snap a picture of the attack on her phone, a form of copwatch that streetworkers have been providing for each other for many years before the term became popular. The copwatching sex worker could not expose herself without also getting arrested. But she texts the photo to the group of sex workers (ideally on a secured email list), and the group responds by providing a safe space of care for the injured sex worker, and pooling together their resources to help her pay for medical bills and find a lawyer that might be willing to take up her case against the police.

We have technologies that can be used to protect us, and also, the same technologies are used to survey us and criminalize our work, whether as activists in a country where the government does not protect essential political freedoms, or as members of a marginalized group whose activities are monitored by the state. Our only protection is in each other, in these informal activist networks. The most important work that we can do is to take care of each other. However, we often reinforce a culture of exhaustion, and when we choose to be silent about our own struggles, believing that they are far less difficult than others’ struggles, we end up reinforcing a kind of silence around these issues, even though our intention is not to load our emotional burdens on others.

“How do we create a culture of care in our activist work so that we are not pushing each other towards burnout and self-neglect?” asked a radical feminist organizer from Spain. “How do we talk to each other about these things, and give each other the permission to take care of themselves?”

Several activists shared stories about how they have colleagues in their early ’30s, already dying of cancer and heartattacks. “In our communities, we witness so much trauma and violence, and we try to hold strong for each other, but we bear the stress on our bodies, and it leaves a mark on us. The body has a very different logic from the mind. all unexpressed emotions and memory – we bear it in our bodies as tension.”

Several Latin American, Asian, and European activists shared stories about how so many of their fellow activists are enduring a life of constant self-neglect, not eating or sleeping well, not taking care of their bodies. In addition to physical illness, a great percentage of activists suffer from mental health injury as well:

“Depression is so common, but we usually force ourselves to ignore it and work past it. There is no time to stop. There is shame in admitting that we are tired, or in stepping back. The activist culture honors a spirit of self-sacrifice. There is a sense that we have to suffer for our work, physically, emotionally, financially – and that is just the way it is. We all work three shifts, with our day jobs and our activism, and as women, with disporportionate duties of care towards our families. And we push each other to be more accountable and work harder, even while we are at our limits as volunteers. And that is just the way that the cultures in our organizations operate. It is a beautiful dedication, but we are suffering for it – it shows on our bodies as we get older, and we get sick.”

Of course, for so many activists, it is often our own trauma and experience with marginalization and darker feelings, which makes us compassionate towards the pains of others, and gives us the drive to fight and build better. But taking care of each other needs to be a part of our activism. “Sometimes we work for years alongside each other, but we still barely know much about each others’ personal lives,” an Italian activist said. “But mutual care is also a political process. It needs to be part of our political process.”

“And it’s important how we phrase that self-care,” said another activist, “Is it because we need to take care of ourselves in order to be able to do better work. Is it for our work? Or can we simply take care of ourselves because we, too, deserve care?”

There is so much guilt involved in admitting to mental unwellness, or taking a step back from activism. It feels selfish. Instead of taking care of ourselves, it would be easier to look out for each other. Understanding the incompleteness that we each share as individuals, we have to take a better approach towards mental health in our work, as we all operate from different positions within a spectrum of wellness, and we need to take care of each other. Building mutual care into our culture is a means towards surviving our activism, and doing more long-lasting and impactful work, but it is also an ends in itself. We need to take care of each other because so many of us desperately need care, and in our small spaces, that care should be the foundation for all our other work.

But how can we exercise mutual care when we refuse to exercise self-care? How can we remind each other about eating better, sleeping better, treating your body and your feelings with greater love and nurturance – when at others’ suggestions of our own self-neglect, we refuse to acknowledge our own needs? In order to do this, we also have to understand self-care as a responsibility, and mutual care as accountability. We have to better embed mutual care into the spaces where we meet and work, not as a fuzzy luxury but as an essential duty towards one another.

The queer disability rights activist, Mia Mingus, wrote beautifully about interdependence. “We are small people, and limited people. We are strong, and we fight. We would rather talk about fighting. Our self-defense workshops are always so much more popular than our self-care workshops. But in defensiveness, we hold on to tension. Every extreme experience is fragmenting us even more, and we have to create spaces for each other to become whole again.”

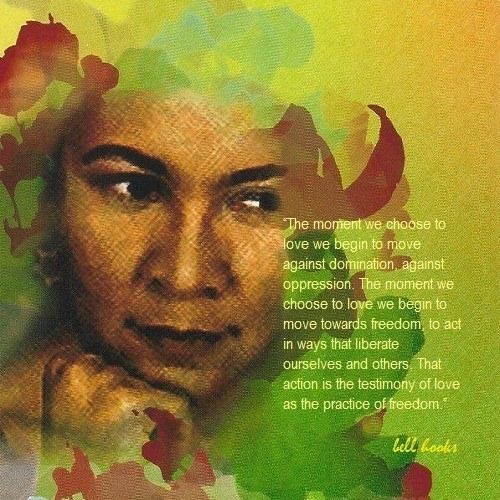

Quoting bell hooks, an elder Bosnian feminist spoke about her years of wisdom in this work: “It’s all about love and our shared fragility.” What we must nurture is a culture of tenderness, of radical love. I admire the loving culture of the domestic worker movement in the United States, and its tender community organizer, Ai-Jen Poo. What a wonderful and radical way, we lead our labor movements! We don’t have to be aggressive or confrontational – without falling into essentialist notions of femininity – I am proud that our movements practice such a radical freedom.

I am reminded of letters from my dear high school friend, an Anarchafeminist historian who is in many ways my role model – I am reminded of an email from her with the words: “Tender comrade.”

I am also reminded of the beautiful of my roommate, an activist who gives so much of herself to care for others. She was the first to introduce me to the writings of Mia Mingus, and I am reminded of how lucky I am to have her friendship in my life. She has taken care of me during times of emotional crisis, and she has always prioritized care, and demonstrated it in every part of her activism. I appreciate her so much.

I feel so blessed to be in a space with such deeply kind and dedicated people; and to have such remarkably giving and tender people in my life. To be an activist is a noble life, in opposition to the selfishness that is assumed to be the most basic drive of human nature and the law of markets – to live in contradiction against that self-serving logic is, in itself, an action against domination, towards building spaces of greater freedom and care.

Listening to the stories of others, I feel I do not give nearly enough. I do not contribute enough work to the collective spaces that I belong to, and I can and should give more, while also taking measure to exercise better self-care and mutual care. I am inspired by the calm and centered spirit of the woman who facilitated this workshop. I want to be that kind of person always: grounded, balanced, warm, and bright. I want to be constantly and consistently creating warmth and providing resources for others, while also fighting together. I am blessed to belong to this marginal part of this world, and I want to improve my way of behaving in these spaces, and treat people with greater tenderness and care. To grow as an activist is to grow as a friend, and to become a better human being. It would be an honor, in this life, to be called an “activist,” and I aspire towards growing as a person, contributing good work, and much much love, so as to deserve such a name.